Crew: One pilot

Capacity: Up to 15 passengers

Length: 13.21 m (43 ft 4 in)

Wingspan:23.47 m (77 ft)

Height: 3.51 m (11 ft 6in)

Wing Area: 48.3 m sq (520 sq ft)

Weight: 2,754 kg (6,072 lbs)

Loaded: 4,536 kg (10,000 lbs)

Useful Load:1,364— 1,818 kg (3,000-4,000 lbs)

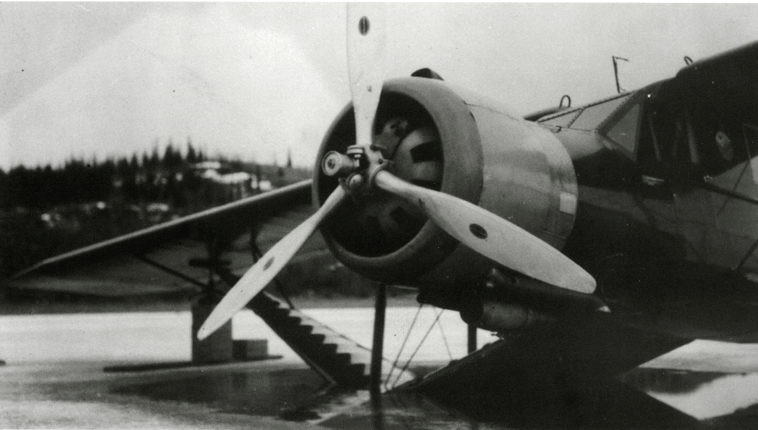

Powerplant: 1 x Wright Cyclone 9 piston radial. 760 hp.

Maximum Speed: 266 kmh (164 mph)

Range: 1,130 km (700 mi)

Service ceiling: 6,700 m (22,000 ft)

Yukon Companies: B.Y.N.

Yukon Pilots: Ernie Kubiecek, Everret Wasson, Buck Stone, Lionel Vines

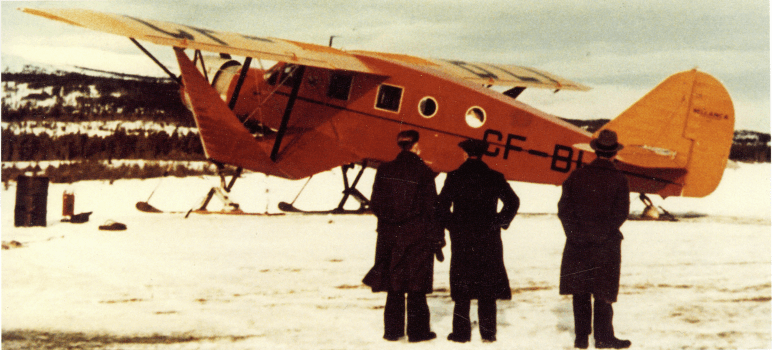

Some aircraft just have style. Examples of aircraft with style include the likes of the P-51 Mustang, the P-38 Lightning, and the Boeing Lodestar, among many others. The Bellanca Aircrusier seemingly drips style. It is large in charge and the struts holding up its wings could almost be mistaken for some form of strange biplane. In fact those struts were designed as a lifting surface, making the Aircruiser a “sesqui-plane” , otherwise known as not quite a biplane.

Fitted with floats the overall dimensions look imposing to say the least. The Aircruiser was a sight to be seen at every one of its stops. The Bellanca Aircruiser pales in comparison in to the likes of the DHC-2 Beaver, or any number of Cessnas in terms of use into the modern age, but that does not mean the strange shaped behemoth was not important.

B.Y.N would purchase their new Aircruiser in November of 1938 from Seattle. Headlines touted “Odd Bird Poised for North!”. It is clear that even in 1938, the Aircruiser made a name for itself in design. The new Aircruiser would not be the performer that B.Y.N. was hoping for ,however. Shortly after arriving in the Yukon the Aircruiser would suffer a catastrophic engine failure. Head pilot, Everret Wasson mid flight had noticed that the oil pressure had dropped from its normal 70 psi to only 40. Upon landing at Fort Selkirk the drain plug was pulled and shards of metal were discovered, a clear sign of internal engine damage and failure. It was later discovered that the main barring of the master connecting rod had disintegrated. The companies new investment now sat lifeless at Fort Selkirk, but that was the least of their worries for this oddly shaped giant.

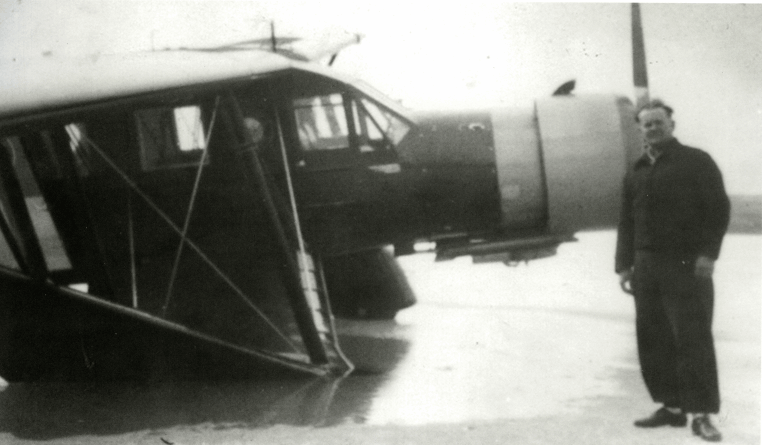

In April 1939, after having its enormous Wright Cyclone engine replaced in the bush in November, the Aircruiser would suffer another misfortune. Lake Labarge was a constant nuisance for the river ships as the river would run clear at both ends of the lake but remain frozen in the lake body , delaying river operations for up to three weeks. B.Y.N. had a novel solution to this problem: have a river boat stationed at the end of the lake towards Dawson. The Bellanca was loaded with a large load destined for the Aksala, a ship docked at the end of the lake. As the 6 ton aircraft taxied to the beached Aksala, the spring ice gave way under one wheel, sinking up to its large diagonal wing strut. Time was of the essence, the spring sun was being reflected off the Aircruiser, further weakening the lake ice. The cargo was desperately unloaded hoping to alleviate the stricken aircraft. Two tons was removed from the Aircruiser but the ice was disappearing just as fast as they could pull cargo from the trapped Aircruiser. For two days a relentless effort was made to save the trapped Aircruiser. Boards, and jacks were strenuously moved from the Aksala to the Aircruiser. Stacks of canned milk which the Bellanca had arrived with, were used in conjunction with the boards and jacks to rescue the large bird from a slow watery grave.

Some aircraft are seemingly destined to suffer a premature fate. No truer words can be said about the beautiful Bellanca. After being rescued from the Ice in April, not two days later a wheel broke off upon landing in Dawson City, the aircraft was damaged but only lightly. The big beauty would be grounded for a short time to make the necessary repairs. In December of 1940 while receiving a minor repair to the skin of the aircraft a spark ignited the fumes of the glue being used. A fire erupted consuming the Aircruiser, the hanger in which it was parked, spare tools and supplies, along with records for B.Y.N.

Like so many of the early aircraft in Yukon Aviation the Bellanca Aircruiser would tragically not survive the harsh realities of early Northern Aviation. Plagued with bad luck at seemingly every go, saved from a watery grave only to be cremated a year later in a hanger accident. Despite being reduced to ash, and bent metal, the Bellanca Aircruiser CF-BLT had the style to endure. The sheer capability and size of this single engined monster were impressive ( when bad luck was not striking it). The Aircruiser proves that sometimes one does not have to be around for a long time to make a name for oneself.

The Yukon Transportation Museum does not own these images and is only using them to illustrate these historic aircraft.